In 1966, an initiative called Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T) put on a series of events in New York that paired artists like Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, and Yvonne Rainer with engineers from Bell Laboratories. It was one of the first major collaborations between the technology sector and the arts, and it was a hit–by 1969, the group had more than 2,000 artist members and 2,000 engineers. By integrating things like video projection, wireless sound transmission, and Doppler sonar into their work, these artists were some of the first to experiment with the boundaries of digital technologies.

An exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery shows just how far, and how fast, the emerging technologies artists use have developed. Along with the works arising out of the E.A.T movement, the ’60s and ’70s saw artists like computer art pioneer Frieder Nake and digital artist Manfred Mohr adopt computer programs to create the first examples of generative artwork. In the ’80s, Nam June Paik brought video into the art world, and the birth of the World Wide Web in 1989 kickstarted a movement of net art that paved the way for contemporary digital artists like Cory Arcangel and Amalia Ulman. These days, digital art has its own biennial, its own galleries and its own displays for hanging in the homes of digital art collectors.

Here, five works from the exhibition highlight the effect that technology and the Internet have had on art over the past six decades.

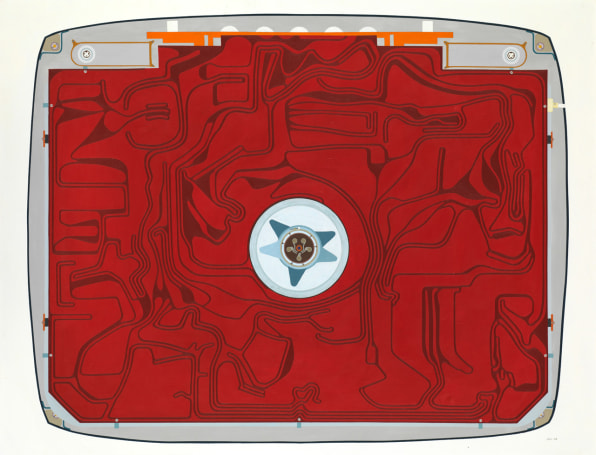

Ulla Wiggen, Den röda tvn, 1967

At the center of the E.A.T. events in 1966 was Ulla Wiggen, a Swedish painter who, like her fellow participating artists, was fascinated by the role of the machine in 20th-century art. Between 1963 to 1969, Wiggen made some 30 paintings that depicted the cross section of electrical appliances like amplifiers and circuit boards and intricately illustrated their inner anatomy.

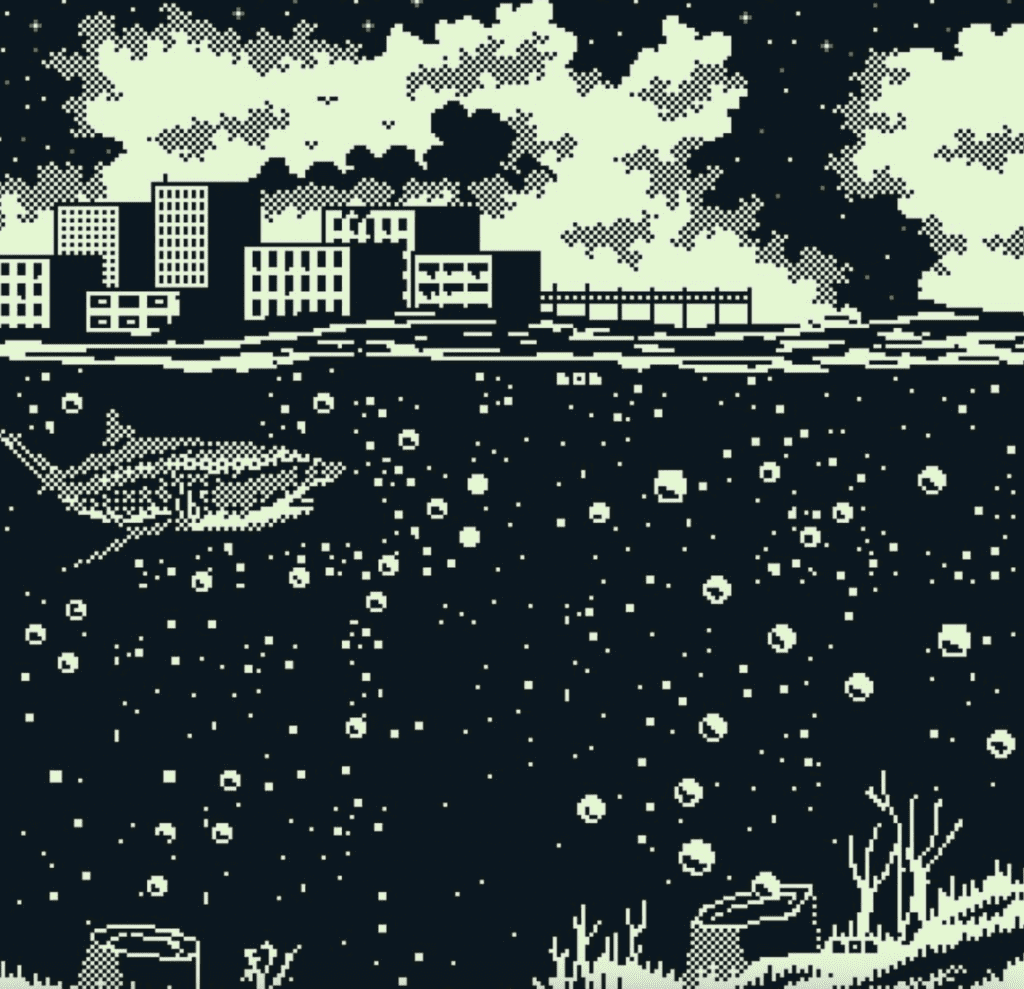

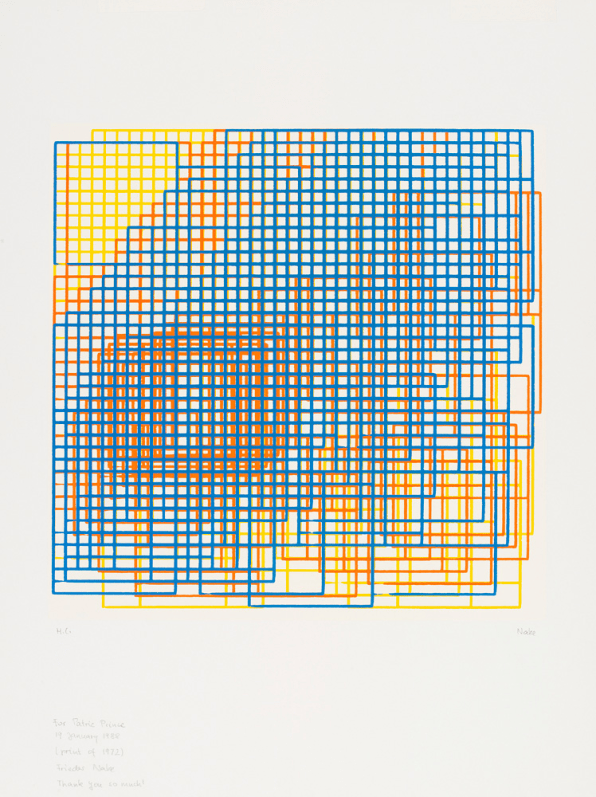

Frieder Nake, Walk-Through-Raster Vancouver Version, 1972

This print by German artist Frieder Nake is one of the first examples of generative art. Nake, a mathematician, computer scientist, and computer art pioneer was known for creating programs that automatically draw prints such as this one. In the early ’70s, the computer Nake was using wouldn’t have had a screen, so Nake used a mechanical device called a plotter to hold a pen or brush and control its movements according to the algorithm.

Eduardo Kac, Tesão (Horny), 1985

Eduardo Kac is a multimedia artist whose work encompasses many genres–from experimental photography and video to BioArt. This is a still from his animated poem, Tesão (“horny” in Portuguese), which was created on the Minitel, a clunky, pre-world wide web computer that connected to telephone lines and was once used widely in France. In the video, words emerge and disappear through layers of lines and blocks of color, forming a sort of ephemeral digital graffiti.

Nam June Paik, Internet Dream, 1994

South Korean artist Nam June Paik is widely considered to be the founder of video art. He once wrote that he wanted to “shape the TV screen canvas as precisely as Leonardo, as freely as Picasso, as colorfully as Renoir, as profoundly as Mondrian, as violently as Pollock and as lyrically as Jasper Johns.” In predicting the global implications of telecommunications, he coined the term that titles the exhibition, “electronic superhighway.” His 1994 work Internet Dream is a video-wall of 52 monitors displaying electronically processed abstract images.

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 18th June 2014), 2015

Over the course of several months in 2014, Amalia Ulman conducted a scripted online performance over her Instagram and Facebook profiles. Mirroring the narratives in extreme makeover shows, Ulman pretended to get breast implants, altered her features via Photoshop, and followed a strict diet. A contemporary example of using the latest tools to navigate a new media landscape, Ulman’s project critiques a cultural obsession with Instagram celebrities and carefully curated online personas. Above is an Instagram post from the project.